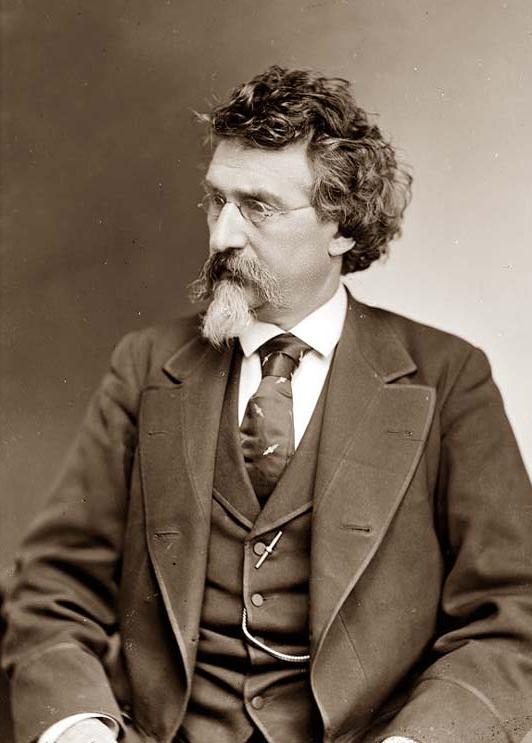

“My greatest aim has been to advance the art of photography and to make it what I think I have, a great and truthful medium of history.”

– Mathew B. Brady

I’m a hopeless history buff and a photography fanatic. As a result, I have my share of historical favorites when it comes to the countless men and women that have carved out a place for themselves in the history of photography. Before I’d even seriously dreamed of getting my hands on my first digital SLR, I had a deep respect and admiration for Mathew Brady.

Granted a lot of this admiration stemmed from my earliest memories of Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln at Disneyland Park, where the idea of having to carefully handle glass plates and dangerous chemicals to take a single photo of the famous President captivated and fascinated me. Regardless, I have always counted this fine gent among my favorites, and have pored over his countless historical portraits and images numerous times throughout my years as a budding photographer.

I recently read “Mathew Brady and His World”, published by Time-Life Books which is mostly a huge portfolio of Brady plates found in the Meserve Collection, but there are little-known facts about the famous photographer’s life and works spread throughout. I learned a lot that I previously didn’t know. So I thought, since this blog tends to be my great mind dumping ground, I would share the most, “Aha! I never knew that!” factoids I discovered.

I recently read “Mathew Brady and His World”, published by Time-Life Books which is mostly a huge portfolio of Brady plates found in the Meserve Collection, but there are little-known facts about the famous photographer’s life and works spread throughout. I learned a lot that I previously didn’t know. So I thought, since this blog tends to be my great mind dumping ground, I would share the most, “Aha! I never knew that!” factoids I discovered.

Here’s the Wikipedia-esque rundown of who Mathew Brady is, for those of you who are unfamiliar. Then I will get on with some interesting factoids that I never knew prior to reading further into his life and legacy.

Mathew B. Brady, born 1822, is one of the most celebrated 19th century American photographers, best known for his portraits of Abraham Lincoln and other political celebrities and his documentation of the American Civil War. I always grew up referring to him as the “Abraham Lincoln photographer”. Conjure up any image in your mind of Abraham Lincoln or the Civil War, and chances up that image carried the “Photograph by Brady” stamp.

So! On with the 10 Interesting Facts About Civil War Photographer Mathew Brady!

1. Brady did not consider himself an artist.

He felt that photography was utilitarian in nature rather than interpretive and creative. Brady was not consciously seeking anything but the clearest, most realistic image he could possibly make, he was unable to conceive of his photography as “art”.

2. All Brady portraits were used with reflected natural light.

Mirrors were often used capture the light from the studio skylights and to create light sources of higher intensity. The light was then controlled further using curtains and screens. This meant that all photography sessions had to be cancelled on dark or extremely overcast days!

3. A Mathew Brady studio would produce around 5 to 6 images a day.

This doesn’t sound so bad, considering old time daguerreotype portraits took for-freaking-ever to take. But just think about it. Brady employed dozens of men on any given day. His studio spanned the upper floor of a building, covering an entire city block. And only given PERFECT conditions and cooperative subjects, Mathew Brady’s studio would produce – maybe – around 5 to 6 images a day. That’s just.. wow.

4. The subject being photographed was immobilized by being strapped in to a long iron bar and neck clamp for the duration of the exposure.

This was a precaution made necessary because of the long exposure time and the propensity of subject to sag, move or wiggle. A half-collar iron clamp clutched the back of the neck, and a metal bar steadied the small of the back. The sturdy metal base is sometimes visible in full length Brady portraits.

5. Brady seldom, if ever, took any of his photographs.

He simply directed the shots and then used “operators” to prepare the plates and work the cameras. Other assistants handled the developing and mounting of the images. Stagehands would move the props and manage lighting mirrors and curtains. For every most Brady images taken, his biggest contribution was just being in the room.

6. Many of the photos that are attributed to Brady today weren’t even taken by his studio or operators.

Many images that carry the “Photographed by Brady” stamp, were actually purchased from neighboring and rival studios for display in the famous Brady Galleries, or published in his Gallery of Illustrious Americans, and have since carried his name as the original photographer.

7. Brady truly is the Father of Photojournalism.

What started as a brisk increase in business, selling portraits to transient Civil War soldiers off to war, ended in his idea to leave the studio and document the war itself, on location. President Abraham Lincoln granted him permission to photograph war scenes in 1861 with the provision that he finance the project himself.

8. Many of the photojournalistic Civil War images attributed to Brady were taken by various photographers on his payroll, when Brady wasn’t even present or on location.

Brady generally stayed in Washington, D.C., organizing his assistants and rarely visited battlefields personally. This often infuriated his hired help, and as a result, he was constantly hiring new camera operators to brave the dangerous battlefields and war scenes.

9. Brady often liked to hide in his own pictures.

Possibly the earliest example of a cameo appearance in an art form, when Brady was on location he enjoyed hiding in random Civil War scenes, almost always with his back toward the lens. In the image above, you can see Brady on the right, leaning against the tree.

10. During the war, Brady spent over $100,000 to create over 10,000 plates. His greatest historical contribution was his financial downfall and he died bankrupt.

Brady expected the U.S. government to buy the photographs when the war ended, but when the government refused to do so he was forced to sell his New York City studio and go into bankruptcy. Congress eventually granted Brady $25,000 years later in 1875, but he remained deeply in debt. Depressed by his financial situation, ruined by a loss of eyesight and devastated by the death of his wife in 1887, he died penniless in the charity ward of Presbyterian Hospital in New York City on January 15, 1896 from complications following a streetcar accident.

How sad for him. He was a genius though, and it seems that too many times, a genius isn’t recognized during his own lifetime. I wonder if the propped up stage actor is John Wilkes Booth? *shudder*

You make me want to go back and look at my history book.That is so amazing .And to put it in black and white did it for me.I feel like him sometimes.I Worry about how broke and penniless I may end up. Sad for him, I wonder if people tried to help him.

Mom! I used your computer and I’m still logged in. You keep commenting as me! haha

Oh, and no, that is John McCullough in the photo. Brady never took pictures of John Wilkes Booth but he did photograph his father on multiple occasions….